by Moriarty.

Listening to Until The Ribbon Breaks music is like catching a shadow, dark and ever-changing. They are songs of passion and frustration, despair and tenderness; to be listened to in dark alleys, on empty roads, while you go off on that adventure you call life. They are a quiet revolution, a plea for a voice heard and a passion felt.

What started out as Pete Lawrie Winfield’s brainchild, writing songs to films silently projected on a studio wall in Cardiff, UK, has grown into something entirely its own; music that transcends expectations of genre and separation between art forms.

I sat down with Pete and Elliot Wall (drums) in their tour van after their show at North Coast Music Festival in Chicago, IL, for a late-night discussion on lust, loss, and life; down the rabbit hole of self-analysis.

stripped: You guys have been really adamant about not wanting to define your music. Do you think that for you is more creatively fulfilling because people do not have an expectation of a certain genre of you?

Pete Lawrie Winfield (vocals etc.): In terms of genre, the name Until The Ribbon Breaks is all about growing up listening to cassettes, making cassettes, taping the radio, whatever song you loved and not caring what genre it was. And then loving it so much that you played it until the ribbon broke. I don’t think we consciously try to make songs influenced by different genres, but we just try not to be concerned with genre. Just make whatever we feel like on the day, basically.

S: You said though, I think it was in Interview magazine, that you purposefully do not want to write love songs because you think that topic has been basically…

P: Played out?

S: Yes, exactly. So are there certain topics you try to mention? Or what topics are not as present in music and art in general as they should be?

Elliot Wall (drums etc.): That’s a good question.

P: You know what, it is a great question, but it is a difficult question. Because, I’d love to sit here and say, yeah I want to sing about current issues and bring politics into music but I never would want songs to feel like it was kind of preachy or saying a certain thing too loud. Having said that, I kind of miss a message in music, I suppose. I kind of regret saying I would never write a love song because it’s kind of mean-spirited, you know. So basically I go into each song not knowing what it will be about and let the music inform it and if it ends up a love song, if it ends up a kind of political message, so be it. I like to let them tell me what they want to be about.

S: Another thing you’ve said is that you’re protective of your image, that basically UTRB is a concept and that you try to be true to that. So how do you find a balance between being a perfectionist and being into what you do, and standing in your own way? Has that been a problem?

P: Christ, that is… You’re like a therapist!

E: I know! She’s got really deep questions. Really good.

P: My God… That is a great question. The answer to that question – I think – is that at the beginning, I think you have some kind of concept, we certainly did, and you want to kind of stick to it and you’re kind of very self-serious about the art and you want people to understand your concept and la-di-da. But as time goes on, from touring it, you realize that you’ve probably taken yourself a bit too seriously and people just want to respond to music and that there is a human connection. And I think the more that that happens the more the concept falls away and you just want to make songs that connect with people. Not to say that there won’t always be a concept, the project itself is a concept. I just don’t want for us to take ourselves too seriously. I think the aim now and in the future is for us to make songs that people like. That’s the concept! Yeah, we’re a concept band; we want to make good songs!

S: Your debut album is called A Lesson Unlearnt. You said that the album name came from trying to unlearn what you had [learned] before and just focus on creation. What for you was the hardest thing to unlearn musically and in life?

P: My own OCDs, really. You can get into a rut musically where you find even like chord sequences that you’re comfortable in and ways of playing guitar that you’re comfortable in and you could write the same song forever, you know? This project was trying to unravel that and go backwards and say, Ok, I’ve done all that, so what… to unlearn your own kind of glass house, green house, you know. In everything you do you find a comfort zone and you kind of get trapped in it straight away. You find a food that you like so you eat it all the time. You find a hobby that you like so you do it all the time. Routine is comforting. So I guess it’s really important to sometimes just pull yourself out of that.

S: I think you can really feel that with Orca, which is one of my favourite songs from the album, because it feels very different, in a certain sense, because it’s so honest. [Editor’s note: Orca is about Pete’s roommate’s death.] So for you writing it, performing it, is it a different experience? Taking something that was such a personal experience in your life and moving it into art?

P: It’s a great question. Orca is an anomaly in the sense that, you’re completely right, it is one song on the record that is purely based on my life, that was incredibly difficult. And funny enough, it is the song that has connected in a way with the most people. Not in a sense that most people bought it or whatever, but in terms of people saying what you’ve just said. And in terms it was a big lesson for the next record and for future song writing, that if you’re vulnerable people connect with that in some way. So you know, it was a really difficult song to write, it’s not like, to be completely honest, I could sit here and say, yeah every time I go on stage I relive that moment, I don’t. In fact, writing Orca was a way of putting a full stop on it and moving on from it. So when I now perform it, it’s a piece of music I enjoy performing, I don’t think about what happened.

E: I haven’t seen you cry to this day.

P: I do think about what happened but not while we perform, it doesn’t take me back in a way, I now just hear the music and enjoy the music.

E: Maybe if you cry, it will bring you back.

P: I can’t force crying! Maybe some tiger balm. Or if you just throw something at me really hard.

S: So of the writing, recording, performing process, what is the hardest for you and what is the most rewarding?

P: Love that question.

E: It was quite hard for me, to sit in a studio and just sit in a studio for that amount of time. But especially with these new songs it’s got easier to work and I now love sitting in a studio, really love it. When we started off writing this next record, it definitely was hard getting into doing it religiously. Going in every day and working your ass off. But once we got moving we were in from 10 a.m. to 2 a.m. every day. I mean the stuff that comes out of it is incredible. I suppose like now sitting in a studio is the most rewarding part. It’s like equal with life whereas before it was like… it’s life, it’s life.

P: I just feel like it’s such a long time to turn the key. We spent so many months thinking like, what do we want the second record to sound like and you make loads of little ideas and none of them work and then suddenly you just go, oh, that’s it. And then now it’s kind of like flowing and I can really hear a record.

E: We definitely learned a lot from touring this record, in terms of like, how to play it to people and watching people’s response. Watching how we feel on stage, you know. When you’re live on stage and you’ve got certain parts… It’s a massive part of the record.

P: Yeah. The first record I was so OCD and concerned with production and how does it sound. And since we’ve been taking it out on the road I notice what bits people like, smile at or are enjoying, and I think like, fuck, what are we doing if we’re not doing that? I hate music that is –

E: Up its own ass.

P: Who cares, you know? Who really cares? Is it going to make someone cry, dance, laugh,…

E: Or run away.

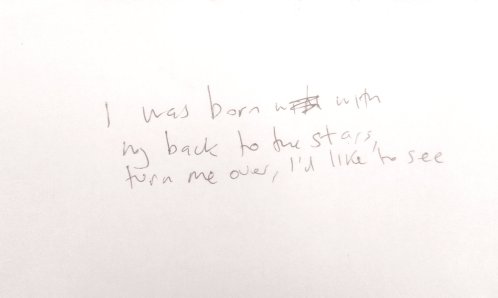

P: For me the most challenging part and the best part is actually the same thing. For me it’s lyrics, mainly. It’s challenging because I question every single syllable, I can’t just write a line and be like, yeah yeah, and right to the next line and be like, fuck it. My rule is that if you read it on a piece of paper, it would still mean something. There’s certain lyrics that I’ve written that I feel like something happened and it hit the moment. I recently went on a train around the country to write lyrics and there was just notepads and notepads of stuff and there was kind of two songs in there. But at least there was two songs. The rest was utter shite. Do you ever write now, with a pen, and think you’ve forgotten what it’s like to write and I’m really bad at it?

E: It’s when I go on tour and I have to sign something and I hold a pen and I’m like, oh shit, I don’t think I’ve held a pen since the last tour. I don’t know what to do with my hands. Which handed am I?

S: So what’s your favourite lyric you’ve written?

P: “I was born with my back to the stars, turn me over, I’d like to see.” I wrote it and I was like, yep. Sometimes it’s difficult to answer that, because you feel like I’m like big-headed or whatever. Equally, some things I write which I think that’s a load of shit, you know, you have to be able to be analytical of your self. But that line in particular I feel like is not trying to rhyme with anything, it’s not because of the next line, I feel like you can write it down on a piece of paper and it doesn’t matter if it’s in a song or not. I also liked “Let’s go shopping for a future, I’ll pick you one.” Because I remember reading this Paul Simon – Paul Simon is my favourite ever lyricist – and he was like beating himself up about this thing, he has always had this kind of weird jealousy of Bob Dylan because you know, they were, to me, the two greatest lyricists ever, so it’s funny that they’ve got this kind of rivalry. What Paul Simon always wanted to do but never could, that Bob Dylan always does, is to be funny. But it wasn’t intentionally a joke, you know, like kind of a smirk. And I feel like with that line I tried to do that. Almost put a joke in there but it’s not a joke.

S: So is the process of writing and being in the studio right now different from before? Because I think you [Pete] said that like, when you wrote the first record you had no stability and it was a place of trying to make sense of what’s around you. Is it different now that you’ve got a following and are living in the sunshine [Los Angeles]?

P: It’s a totally different now writing with El. One of them is a song where the hook is like “when the light gets through” and I really, there’s a real sense on this record of positivity and a light on the end of a tunnel. The first record was so, kind of, you know I wrote it on my own and it was right at the time at the beginning of the process I was like sleeping on the studio floor and had no money and la-di-da. I still have no money, but there’s a, I don’t know, bit of a more arms-open record coming.

S: So you don’t need to be desperate and sad to be an artist? That’s kind of hopeful.

P: You know, sometimes I worry that I’m too happy.

Stay tuned for Part 2, when we talk about the good things in life: festivals, pizza, sex and…that’s about all you need, really.

Pingback: stripped off: Until The Ribbon Breaks. Part 2: Midnight Rambler | stripped·